Swinging Trapeze and Cloudswing

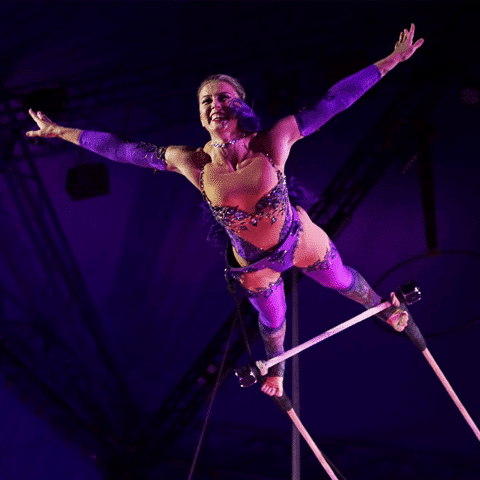

In Part 1 of this four-part series, I spoke about the factors which influence the height of a swing, how to gain height and how to use the gravitational pull efficiently. We also know that more weight increases the potential to gain height and maintain it, this is another reason why swinging trapeze bars have extra weights on either side of the bar. The main reason is to keep the trapeze bar as stable as possible when the student drops from above the bar to below it. However, cloudswing has no extra weight, and students of cloudswing accept that it will be more difficult to build swing height, but this is an acceptable sacrifice for the comfort of the soft rope against their body. The laws of physics do not discriminate, and all swinging acts face the same challenges to gain and maintain height. It’s therefore up to the student and their coach to find the most efficient way to achieve the skills while continuing the struggle of maintaining and gaining height. These swings are regarded as single plane pendulum, with the swing going in only a forwards and backwards direction due to the attachment points and the nature of the act.

Swinging trapeze performers push up their swing while in a standing position. They will bend and straighten their legs while moving in both forwards and backwards directions. This action alone does not change the length of the pendulum, but it can change the speed of the pendulum. The student’s weight distribution on the trapeze bar, relative to the direction of their swing, (leaning forwards, or backwards relative to the ropes or point of contact), helps generate more speed, and the bending of the ropes also shortens the length of the pendulum a little. By bending down just as they start to drop down from the highest point of their swing, their body weight adds to the gravitational pull resulting in achieving more speed. Then, by violently pushing their legs straight after the bottom of their swing, they are adding more speed to the natural momentum of the swing. Standing up quickly between the ropes when they reach the full height of the pendulum, their weight is distributed as close to the bearing points as possible, which also reduces the gravitational pull on the heaviest part of the pendulum, allowing the trapeze bar to go a little higher. Good technique and timing fine tunes this action. Once the pendulum has reached a 180-degree angle (full height), it does not require much effort to maintain this height. Full height is relative to the length of the cables/ropes of the trapeze, so the maximum height gained at 180 degrees is equal to the length of the cables (if you have 4m long ropes on your trapeze, by the time you have reached 180 degrees, you will have gained 4m of height relative to the ground.)

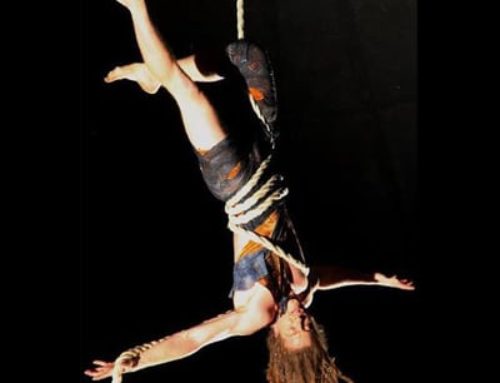

Swinging trapeze mostly consists of skills when the student is hanging under the trapeze bar by their hands, knees or ankles. In these cases, the pendulum is lengthened, which ultimately lowers the height of the swing, so skills under the bar are limited to the minimum amount of swings necessary, to avoid losing too much height. Skills learned from the hand hanging position are more difficult since it requires the full length of the student’s body to be moved a large distance in a very short window of time. Precise timing and strength to return onto the top of the trapeze bar during the swing is required. Techniques created using precise timings, strength and speed have increased the vocabulary of swinging trapeze in recent years. The way the student can move their body from above to under the bar and back to above the bar is done by the use of a secondary pendulum created by the student using their body. When timed to the top of the swing (where the pendulum is going at its lowest speed), spins and somersaults are achieved, mid-air, before landing back on top of the trapeze in either a sitting or standing position. The secondary pendulum of the human body uses the changing of direction of the pendulum at its peak to achieve these great changes of length of pendulum.

The cloudswing is very similar to swinging trapeze, but here the student can also gain height by “pumping” their swings from a semi knee hang position with their hands still on the rope. The “pumping” action increasing speed and changes the length of the pendulum to gain height. This is an efficient way for cloudswing students to gain height compared to swinging trapeze students who have the weighted bar to help with gaining height. On the cloudswing, skills are initiated from the student’s knees, lower back, hips, ankles and very rarely from hands. Similar twists and somersaults can also be achieved on the cloudswing as on a swinging trapeze, despite the lack of bar weight. Wrapping the rope around the legs is something only achieved on a cloudswing. By doing the wrap, the student has shortened the length of the pendulum, increasing the potential to gain swing height with less effort. Due to the speed that height can be lost during a routine, the sequence of skills is limited to only a few swings so that the student does not lose too much height, which needs to be built up again before the next sequence. This is another benefit of doing skills at full height is that it is easier to regain height lost by the end of the sequence.

Sadly, there are not many swinging trapeze and cloudswing students due to the rigging requirements and the fact that they also need a competent person holding their safety line. I look forward to teaching more students on these disciplines, despite the lack of contracts for them. They are still a fun discipline to learn and master and to enjoy the adrenaline rush which always comes with any swinging. One of my favourite things to do is to achieve full height, then hang back on my arms while sitting, and close my eyes and enjoy the sensation of the movements of the swing. Have fun and swing high.